Geoffrey Bawa: Sri Lanka’s Iconic Architect

Behind Edwards Collection’s Tropical Elegance

Discover how Geoffrey Bawa’s revolutionary tropical modernism lives on through Sri Lanka’s finest architectural spaces from national landmarks to the luxurious Edwards Collection boutique villas. This immersive blog explores Bawa’s philosophy, iconic works, and how his spirit shapes contemporary design for conscious travelers.

There is an unbreakable bond between the island nation of Sri Lanka and the work of its most famous architect, Geoffrey Bawa.

“Every artist works on a different scale. A page. A painting. A sonata. A film. A novel. A house. A garden. But essentially they all create, in some ways, self-portraits of themselves. Art is a long intimacy. The scale of the achievement might be grand and take years but it has to be personal and carefully pieced together and specific to its culture.” – Michael Ondaatje

Born in 1919 in British-ruled Ceylon, Geoffrey Bawa was the son of a successful Moslem lawyer and a mother with mixed Dutch Burgher ancestry. Geoffrey Bawa was brought up in a prominent Sri Lankan family. He travelled to Britain in 1938 to study English at Cambridge University and then law in London. He briefly practiced law in Colombo after returning to Ceylon in 1946. But after his mother passed away, Bawa gave up practicing law and set out on a two-year journey of extensive travel.

After Ceylon became independent in 1948, he went back home and bought a run-down rubber plantation in Lunuganga, close to Bentota, with the intention of transforming it into a tropical version of an Italian garden. Bawa enrolled in an architectural apprenticeship with H.H. Reid in Colombo after realizing that his lack of technical knowledge was impeding his goals. Bawa attended the Architectural Association in London following Reid's death in 1952, and at the age of 38, he became a licensed architect in 1957.

Geoffrey Bawa became seriously disabled after a string of strokes in the early 1990s. His impact on architecture persisted despite his deteriorating health. At the age of 83, Bawa passed away on May 27, 2003, leaving a legacy that still serves as an inspiration to architects everywhere.

Did you Know?

The White Book: He remained relatively unknown outside his native land in 1986, however, when concept media, the Aga Khan’s publishing house of Singapore, brought out the monograph of Geoffrey Bawa, known familiarly as the “White Book”. The White Book also encouraged pastiche Bawa.

Father of Architecture in Sri Lanka; Bawa’s Legacy

Celebrated as the father of Sri Lankan architecture, Geoffrey Bawa transformed the built environment of the island by creating a unique architectural language that balanced modernist principles with regional customs, cultural heritage, and the tropical climate. His innovative style, sometimes known as "tropical modernism," was inspired by Sri Lanka's natural beauty and climatic conditions, guaranteeing that his works were both aesthetically beautiful and suitable for their surroundings.

Bawa was labelled "tropical modernist, romantic, vernacularist, and regionalist" due to his roots in local sensibilities. However, he resisted being confined and avoided describing his methods or defining his practice.

His legacy lives on as evidence of his belief that architecture is an art form that unites the natural and the constructed, the past and the present. By his revolutionary contributions, Bawa not only changed Sri Lanka's architectural identity but also made a name for himself as an inspiration on the international architectural scene.

Design Philosophy: Bawa treated every project as though he were creating it for himself, developing a strong sense of empathy for his customers and frequently working closely with on-site artisans to improve designs as they were being built.

Ins and Outs of Architecture: The complexities of architecture, as demonstrated by Geoffrey Bawa, reveal a philosophy that embraces a harmonious interaction between form, function, and environment, going beyond simple construction. Bawa was a master of spatial fluidity and experiential design, and his method was characterized by a profound respect for context, climate, and culture.

Influence on Sri Lankan Architecture: Bawa embraced experimentation and improvisation, a valuable skill that served him well when imported building materials were scarce in the country during the 1960s.

Tropical Modernist Movement: The architectural style known as Bawa's Tropical Modernism blends modernist ideas with the unique requirements and circumstances of tropical settings. His method focuses on creating open, airy spaces that adapt to the local climate, emphasizing the smooth integration of buildings with their natural surroundings.

Tropical Modernism: Bawa's Architectural Philosophy Bawa believed architecture should be a dialogue with nature. His signature style involved open courtyards, flowing indoor-outdoor transitions, and the use of natural materials like stone, timber, and terracotta. More than just buildings, Bawa created experiences serene, sustainable, and grounded in local identity.

Edwards Collection: A Living Tribute to Bawa's Vision

The Edwards Collection of luxury boutique villas in Sri Lanka pays homage to Bawa's timeless principles. These properties are not merely accommodations; they are curated spaces where architecture, culture, and landscape exist in perfect harmony. Here’s how Bawa’s legacy is beautifully echoed in each villa:

THE FRANGIPANI TREE – Thalpe by Edwards Collection

Designed by Channa Daswatte, protégé of Geoffrey Bawa

A beachfront sanctuary and one of the finest Bawa-inspired hotels, where minimalist architecture meets tropical elegance. Designed by Channa Daswatte one of Sri Lanka’s most renowned architects and a protégé of Geoffrey Bawa, it is infused with Bawa’s philosophy of understated luxury and harmony with nature.

Set against the golden sands of Thalpe, this villa blends contemporary design with natural elements, creating an intimate escape shaped by frangipani trees, open-to-nature bathrooms, and sweeping ocean breezes.

Why it Reflects Bawa:

Oceanfront Setting: Uninterrupted views of the Indian Ocean, merging the indoors and outdoors in true Bawa style.

Frangipani Serenity: The villa is wrapped in blooming frangipani trees, offering an atmosphere of calm and tropical beauty.

Infinity Pool: A seamless pool facing the sea, inviting you to relax in nature’s embrace.

Eco-Sensitive Design: Constructed using local materials and techniques that respect the natural surroundings and community.

"Nature-Inspired Luxury

Enjoy the rare experience of watching turtles in their natural habitat a gentle reminder of The Frangipani Tree’s commitment to thoughtful, immersive travel"

PARK STREET BY BAWA, COLOMBO

Also known as Jayakody House, Colombo (1991–1996)

Did you know the story behind the Rohan Jayakody House? It’s one of Geoffrey Bawa’s most fascinating private commissions designed at the height of his architectural maturity, yet shaped by an unlikely connection to Sri Lanka’s political elite.

The story begins with Rohan Jayakody, who was married to Dulanajalee Premadasa, daughter of President Ranasinghe Premadasa. It was the First Lady herself who personally convinced Bawa to take on the project a request that the master architect, known for his selectiveness, accepted with quiet certainty.

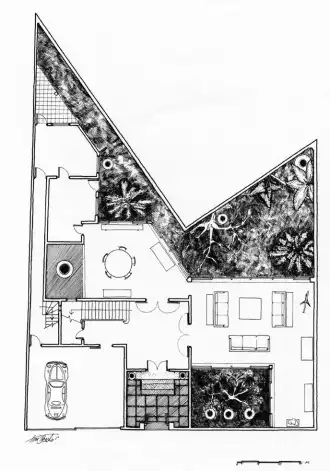

Bawa was tasked with transforming an awkward, oddly shaped 450-square-metre plot (18 perches) tucked inside a cul-de-sac on the edge of Colombo’s busy Union Place business district. The environment may have been hostile, but what emerged was a retreat defined by sophistication and restraint.

At its core, the design is a tower–courtyard hybrid. From the street, the house appears discreet and understated its blank façade interrupted only by a pair of garage doors and a subtle entryway. But stepping inside, the space unfolds into a layered experience.

The ground floor houses reception rooms that open into small garden courts, evoking an almost subterranean atmosphere. The dining room, partially illuminated by a blue-painted ventilation shaft, adds an unexpected wash of mood and shadow.

On the first floor, each principal bedroom is paired with its own private courtyard an intimate nod to Bawa’s deep understanding of privacy and nature. The second floor offers a large terrace, partially shaded by a soaring loggia, ideal for quiet reflection or urban escape.

Crowning the home is the third floor, where a small swimming pool and open terrace reveal sweeping views across Colombo’s rooftops, all the way to the city’s central park.

With the Jayakody House, Bawa once again proved that even in the most constrained spaces, architecture could breathe, expand, and connect offering its inhabitants not just shelter, but serenity.

Why it Reflects Bawa:

· Use of natural light to enhance ambiance.

· Earthy materials and textures creating timeless elegance.

· Transformation of a bustling urban area into a tranquil space.

"Among his lesser-known yet architecturally significant works is the Jayakody House a gem tucked away near Park Street, Colombo"

The Hermitage – Kandy by Edwards Collection

Designed by Channa Daswatte, protégé of Geoffrey Bawa

Positioned on the edge of the Victoria Reservoir, The Hermitage offers breathtaking views and a tranquil escape, where architectural elegance meets nature’s quiet rhythm. Designed by Channa Daswatte, a distinguished protégé of Geoffrey Bawa, this retreat embodies the essence of tropical modernism. The villa’s minimalist design, framed by forest, water, and open space, reflects Bawa’s enduring influence seamlessly blending natural materials with thoughtful spatial flow to create an atmosphere of serene sophistication.

Why it Reflects Bawa:

· Seamless integration of indoor and outdoor spaces.

· Mountain and Lake view

· Use of earthy materials like stone and wood.

· Emphasis on natural ventilation and light

· Library with collection of rare books

· Surrounded by nature; an occasional glimpse of birds, monkeys, wild boar, deer and many more

THE TOWER BY GEOFFREY BAWA COLOMBO

At the beginning of the 1960s Bawa had built a simple pavilion house for Pin and Pam Fernando on a fairly small plot in a short culde-sac off Kannangara Mawatha now Alexandra Place. Bawa had been experimenting with tower houses ever since completing the house for Peter Keuneman and had recently added a tower to his own house in 33rd Lane. He tucked the new house into a corner of the Fernando’s' garden and let it grow up between the branches of a tall bo tree. Visitors arrive at a porch at the end of the cul-de-sac and are led via a long toplit tunnel to the base of the tower. Kitchen and dining room are on the ground floor, the sitting room is on the first floor, the bedroom is on the second floor and the top floor is given over to a roof terrace. All four levels are linked by a simple concrete staircase with metal handrails, and a double-height void connects the dining and sitting rooms.

As well as offering an alternative prototype for the tropical urban house, The Tower by Bawa is important because it is spatially innovative. It is also an example of a new 'stripped-down' aesthetic that would reappear in Bawa's work with increasing frequency, signifying his growing irritation with being pigeon-holed as a vernacularist.

Tastefully furnished with a sprinkling of rare antique Ebony furniture and a few pieces of Modern Furniture, The Tower by Jeffrey Bawa is Ideal for a couple or family of three. The Tower by Bawa is located just meters away from the Viharamahadevi Park, the Town Hall and minutes away from the City Centre, Restaurants, and every other attraction a Cosmopolitan City like Colombo has to offer. The Tower by Jeffrey Bawa Invites you to enter an era where buildings were a work of art rather than an empty impersonal space.

Why it Reflects Bawa:

- Architectural minimalism elevated a vertical retreat balancing simplicity with elegance.

- Curated material palette raw concrete, polished cement, and antique woodwork echo Bawa’s signature restraint.

- Light-play and shadow strategic openings create evolving moods throughout the day.

- Sanctuary in the city an introspective escape just ten minutes from Colombo’s urban core.

- Ideal for quiet creatives and mindful travellers whether couples or business guests seeking calm sophistication.

“Architecture is the art of reconciliation between ourselves and the world.” – Geoffrey Bawa

Beyond the Villas: Bawa's National Legacy

While Geoffrey Bawa’s touch graces many serene villas like those in the Edwards Collection, his legacy extends to Sri Lanka’s most iconic public landmarks. These masterpieces exemplify his ability to weave cultural heritage, landscape, and function into architectural poetry.

Sri Lankan Parliament – A Floating Symbol of Democracy

Positioned on an artificial island in Diyawanna Oya, the Sri Lankan Parliament is one of Bawa’s most celebrated civic designs. Completed in 1982, it reflects the harmony between governance and the natural world a serene, grounded space where architecture serves both authority and accessibility.

Why it Reflects Bawa:

· Designed to float gently within its lake setting, emphasizing balance and peace

· Inspired by ancient Sri Lankan structures with terracotta roofs and timber accents

· Emphasizes cross-ventilation, natural light, and sustainability

· Symbolizes unity and democracy through its central, accessible placement

· A modern institution enriched with traditional Sri Lankan soul

University Of Ruhuna – Learning In Harmony With The Land

Set against the undulating hills of Matara, the University of Ruhuna is a testament to Bawa’s belief that architecture should follow the rhythm of the land. Designed to enhance education through spatial experience, it offers inspiring views, breezeways, and fluid transitions between indoor and outdoor space.

Why it Reflects Bawa:

- Structures cascade along the hillside without disturbing natural contours

- Framed views, verandas, and courtyards encourage interaction with nature

- A masterclass in passive cooling and contextual architecture

- A campus that feels more like a sanctuary than an institution

Lunuganga Estate – Bawa’s Living Masterpiece

Once a dilapidated rubber estate, Lunuganga became Geoffrey Bawa’s lifelong creative laboratory. Located near Bentota, it evolved over 40 years into a dreamscape of gardens, pavilions, courtyards, and carefully framed vistas—a place where architecture, art, and landscape are in constant conversation.

Why It Matters:

- Every path, pond, and pavilion reflects Bawa’s personal design evolution

- Blurs boundaries between house and garden, structure and scenery

- Often called a ‘living self-portrait’ of Sri Lanka’s greatest architect

Number 11, Colombo – Geoffrey Bawa’s Living Residence

Tucked away in the quiet lanes of Colombo’s Cinnamon Gardens, Number 11 was Geoffrey Bawa’s personal home and design studio. What began as a modest house in the late 1950s gradually evolved into a layered, introspective space, merging indoor and outdoor areas, private courtyards, and curated light in ways that reflected Bawa’s deeply personal approach to architecture.

Number 11 is often referred to as a living museum, not just for its preserved interiors filled with art, tropical plantings, and eclectic furniture but for how it represents Bawa’s design philosophy in motion: understated elegance, spatial storytelling, and the seamless blending of nature and built form.

Now maintained by the Geoffrey Bawa Trust, parts of the home are accessible to the public through guided visits. While the space remains small in scale, it offers a rare opportunity to observe how Bawa designed for living, working, and dreaming all within a single, thoughtfully composed structure.

Embracing Minimalism: A Harmonious Blend of Design, Sustainability, and Nature

A View Across Minimalistic Design

The majority of people believe that a minimalist design is one that simply eliminates all elements. It prioritizes clean lines, open spaces, and a limited colour palette to create a sense of clarity and tranquillity. The goal is to create designs that are aesthetically pleasing without being cluttered or overly complex.

Geoffrey Bawa's work, while not strictly minimalistic in the traditional sense, aligns closely with the principles of minimalistic design through his emphasis on simplicity, functionality, and integration with the environment. Bawa’s designs often feature clean lines, open spaces, and an efficient use of materials, creating a sense of calm and serenity in his buildings.

In his personal spaces, such as Lunuganga and Number 11, Bawa strips away unnecessary ornamentation, focusing on natural elements and the thoughtful arrangement of space. His architecture embraces the idea of minimalism by focusing on the essentials, allowing each element to serve a purposeful function within the design. The incorporation of nature, light, and air is central to his work, echoing minimalistic principles of openness and clarity.

Thus, while Bawa may not be considered a minimalist architect in the strictest sense, his work shares the core values of minimalistic design, offering a harmonious balance between built structures and the natural world, with an emphasis on simplicity and beauty in every detail.

Minimalism with Meaning While Bawa was not a minimalist in the traditional sense, his restraint and intention set him apart. Every door, corridor, or window was placed with purpose. Simplicity was never empty; it was mindful.

Environmental integration

Bawa's work emphasized harmony with the environment. His designs often sought to minimize the impact on nature and integrate the built structure into the surrounding landscape. This could involve orienting buildings to take advantage of natural light, local materials, and the site’s natural features like trees or water bodies. Bawa’s approach created a sense of continuity between the architecture and the environment, as seen in his famous projects like The Frangipani Tree, where the building is embedded into the landscape to maintain a sense of place.

Sustainable Architecture

Bawa was ahead of his time in terms of sustainability. He designed buildings that responded to local climates, used sustainable building materials, and promoted passive cooling techniques. For example, he utilized large overhanging roofs and strategically placed windows for natural ventilation, reducing the need for air conditioning. His use of local stone, timber, and clay tiles also minimized environmental impact. These elements of his design not only suited the climate but also reflected a sustainable and respectful approach to local traditions and resources.

Seamless indoor outdoor flow

One of Bawa’s signature elements was the seamless integration of indoor and outdoor spaces. His buildings often feature open courtyards, verandas, and large windows that allow natural light and air to flow through. By breaking down the boundaries between the interior and exterior, he created a fluid, continuous experience. This approach also made the most of the tropical climate, where outdoor living is possible year-round. An example is The Lunuganga Estate, where Bawa designed rooms that open into the landscape, allowing nature to become a part of the interior space.

Sustainability Before It Was a Trend: Long before green architecture became fashionable, Bawa designed for sustainability:

- Cross-ventilation over air-conditioning

- Locally sourced materials

- Buildings that grow from the land, not on it

Bawa’s Greatness and Exclusivity

The word “Architect” however is derived from Greek means literary the leader of the builders. Bawa is truly a leader in his days. The brilliance of Geoffrey Bawa's architecture is found in the way he skillfully combines modernism with Sri Lanka's diverse cultural and natural heritage. His creations are enduring examples of the strength of design that honors heritage, the natural world, and the human condition. Bawa redefined tropical architecture with unmatched elegance by incorporating buildings into their natural environments, encouraging sustainable practices, and designing areas that blur the lines between indoor and outdoor living. Bawa redefined tropical architecture with unparalleled elegance.

The Edwards Collection, with its dedication to refined elegance and cultural authenticity, resonates deeply with the artistic legacy of Geoffrey Bawa. Much like Bawa’s architectural philosophy, these boutique properties weave together minimalism, environmental harmony, and a deep respect for local culture.

He designed for emotion, not just function. Bawa said he wanted his buildings to "reveal themselves slowly" turning corners, layering light, and surprising the visitor with framed views

Michael Ondaatje's words aptly capture this connection: art, whether a garden, a house, or a collection of boutique hotels, is an intimate self-portrait, carefully pieced together to reflect personal vision and cultural identity. The Edwards Collection not only celebrates the timeless influence of Bawa but also extends his legacy, creating immersive experiences that honor both artistry and place.

Why Edwards Collection Celebrates Bawa

Each villa offers a chance to experience Geoffrey Bawa architecture stays, where every element is a reflection of his design legacy. It is a poetic continuation of Geoffrey Bawa’s design language. These spaces are not only architecturally significant but emotionally resonant. They invite guests to slow down, reconnect, and experience Sri Lanka in its purest form.

Michael Ondaatje once said, "Art is a long intimacy." At Edwards Collection, that intimacy lives on from the rustle of coconut trees to the curve of a stone wall.

Inspired by Bawa? Now experience it for yourself. Browse our curated collection of luxury boutique villas in Sri Lanka and step into a world where architecture meets artistry. Whether you’re seeking creative inspiration or peaceful reflection, these tropical modernist getaways in Sri Lanka invite you into Bawa’s world one villa at a time.

Explore All Villas by Edwards Collection | Contact Us